Pliny the Elder is a fascinating beer, and not only for the fact that it is an incredible IPA. There is such an allure, mystique, and reverence for this beer.

It is one of the highest rated IPAs in the world. Despite it’s year round availability, it never seems to be available in its distribution markets. And when it is available, retailers often limit the amount that can be purchased at a time, or, it is hidden in the back and must be requested for by name, possibly with some sort of secret password. Combined, this makes it a sort of liquid gold amongst craft beer enthusiasts.

Is Pliny that significant? Are there no other IPAs that are as good as Pliny? Is it truly, a one of a kind beer that cannot be recreated by any other brewery than Russian River? When you word it like that, it begins to sound ridiculous. Of course there are other incredible IPAs that are just as good as Pliny, so why the hype? Answer: It’s always fresh.

How much, exactly, does freshness matter? If you travel deeper into the inner craft beer circles, you’ll start to hear the purists declare that Pliny should only be consumed within 30-45 days of bottling. They say that it has to be as fresh as possible, otherwise it’s not as good. But the same can be said for any IPA. As I mentioned in my aging guide, hop aroma and bitterness fade rather quickly. Being as the whole point of an IPA is the hops, it makes sense that the fresher it is, the more vibrant the aroma and flavor is.

Owner Vinnie Cilruzoe is extremely cautious of growing too fast, to the point where Russian River’s slow growth is causing an exponential expansion in demand for their beers. But this has ensured that the hop forward beers, like Pliny the Elder, don’t sit on the shelf very long, meaning that if you are lucky enough to find it, it is likely to be extremely fresh.

Stone Brewing Company is another brewery that comes to mind that emphasizes how important freshness is. They have repeatedly stated that none of their year-round beers should be aged. The above image can be found on the back of their IPA bottles. The above link serves as a method for consumers to report Stone beer that was not available within the ‘best by’ date. Most notably, this past summer Stone released a new IPA titled “Enjoy By XX-XX-XXX,” with the ‘X’s’ being replaced with a specific date. Stone has a significantly larger distribution map than Russian River does. To ensure that Enjoy By is available as fresh as possible, Stone limits each batch to only 2 or 3 markets at a time, determined by consumers voting at the Enjoy By site.

To clarify however, Pliny the Elder is an amazing IPA. It has a sweet, lemony nose with a rich piny taste. Pliny has a crisp, light body, likely from using an addition of sugar in the boil. The freshness factor definitely helps, as it accentuates the pine and citrus flavors. But even if you drink a bottle 2 months past bottling, it is still a fantastic IPA.

If you want a clear example of how important freshness is in beer, visit one of our local breweries, like Tenaya Creek, Big Dog’s, or Chicago Brewing Company. There is no travel time in the beers that are served at these brewpubs. The beer is brewed and served on premise, making it the freshest beer you can find. Joseph James is another local brewery that makes a fantastic IPA. While they don’t operate a brewpub, their beers still have a very short travel time to our local retailers. You’ll notice that IPA’s from all of these breweries have an aroma and bitterness unlike most other IPA’s available in our state that were distributed from somewhere else.

For more information in understanding freshness and aging, check out our aging guide.

Sour beers, while they may have more history than any other beer style, are quickly emerging to becoming quite the trend here in America. I’m going to take a quick moment to briefly explain what makes a beer sour, and describe some of the more common styles of sour beer.

Hopefully you’ve read my Science of Yeast articles. In the second article, I explained the chemical equation for the fermentation of sugar into carbon dioxide and ethanol. The third article ended by briefly explaining the existence of wild yeasts and bacterias that are sometimes used in beer production. To put the two together: while the Saccharomyces strain of yeast will consume sugar and turn it into alcohol, there are other microscopic organisms that will consume proteins and nutrients and turn them into acid, typically lactic acid. Lactic acid is sour, as you should know if you’ve ever eaten plain yogurt.

American breweries that are making sour beers are typically adding very specific bacterias into their beer to produce lactic acid. The most common bacterias used for this process would be Pediococcus Damnosus and Lactobacillus Delbruckii. While this makes for an exacting, and nearly reproducible, product, traditional sour beers were never made this way…

Traditional Belgian lambics are one of the most fascinating styles of beer. Rather than adding a single and sterile strain of bacteria, they simply let the beer ferment spontaneously. That is, once the beer is brewed, the hot wort is transferred to a coolship in the attic. A coolship is basically a large, shallow pan that is left wide open. The windows in the cobweb filled attic are also left wide open, to allow the Belgian air to pour in and cool the hot wort. The beer is then transferred off into barrels and left to ferment. While the beer was left exposed overnight in the coolship, as many as a few hundred different strains of yeast and bacteria enter into the beer. This collection of living organisms will ferment and acidify the beer over the next several years. Due to the cornucopia of yeasts and bugs that are added to coolships, very few American sour beers can even come close to the complexity of a Belgian lambic (however it is worth mentioning that there are a couple American breweries who also spontaneously ferment their beers).

Once the lambics are stored in barrels, the brewers will then age these beers for several years, occasionally offering different vintages for sale. The younger lambics have a sharp sourness to them. As they age, they stay sour, however they become balanced out with the other phenols and esters that are produced by the various yeasts present in the beer.

Guezue is the holy grail of sour beers. A gueuze is a beer made by blending one year, two year, and three year old lambics together. This creates a beer that not only features the sharp sourness of a fresh lambic, but also the smoothness of an aged lambic. Guezue is one of the most complex beers that I have ever tasted, with different layers of flavors present in each sip.

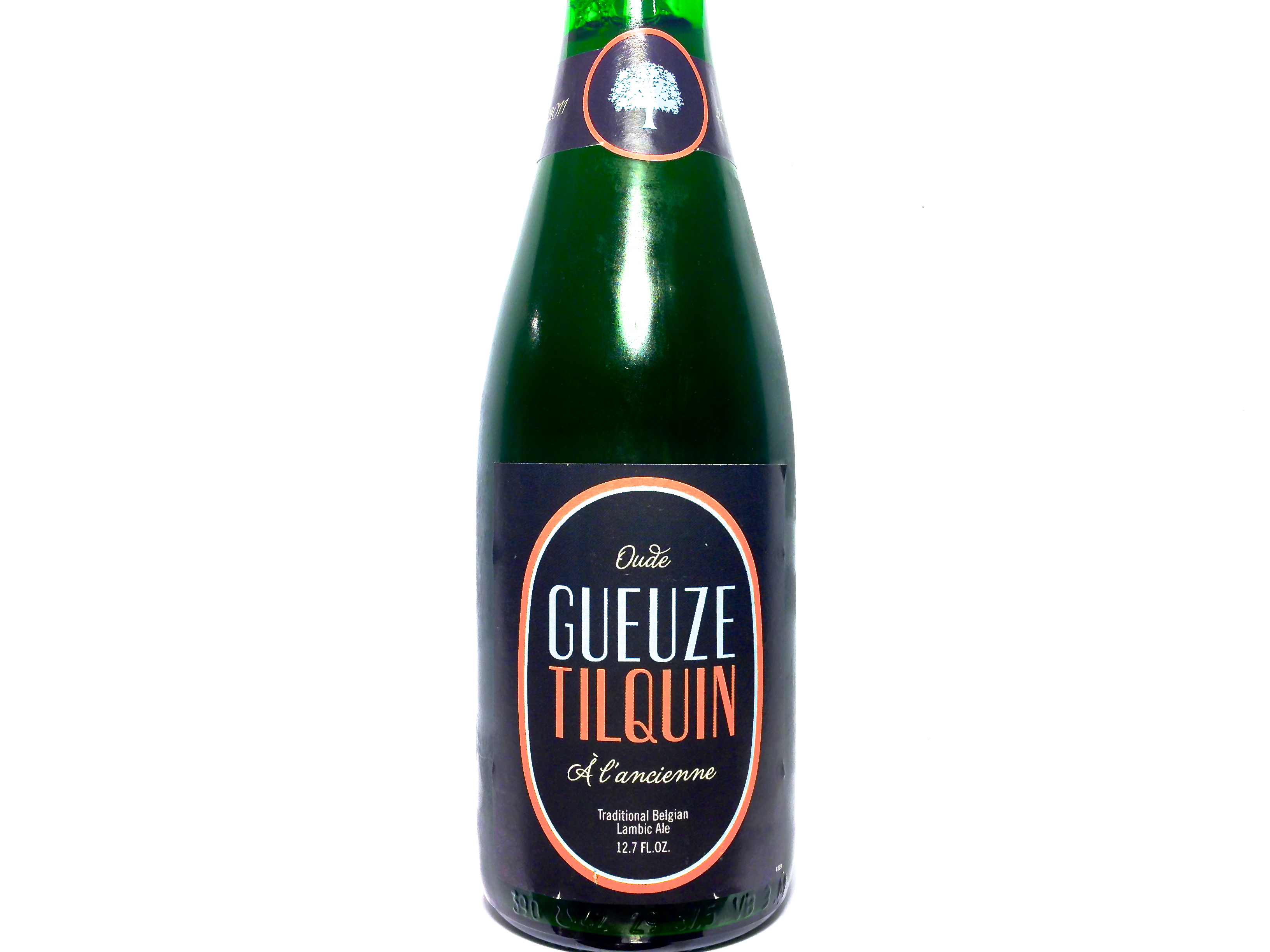

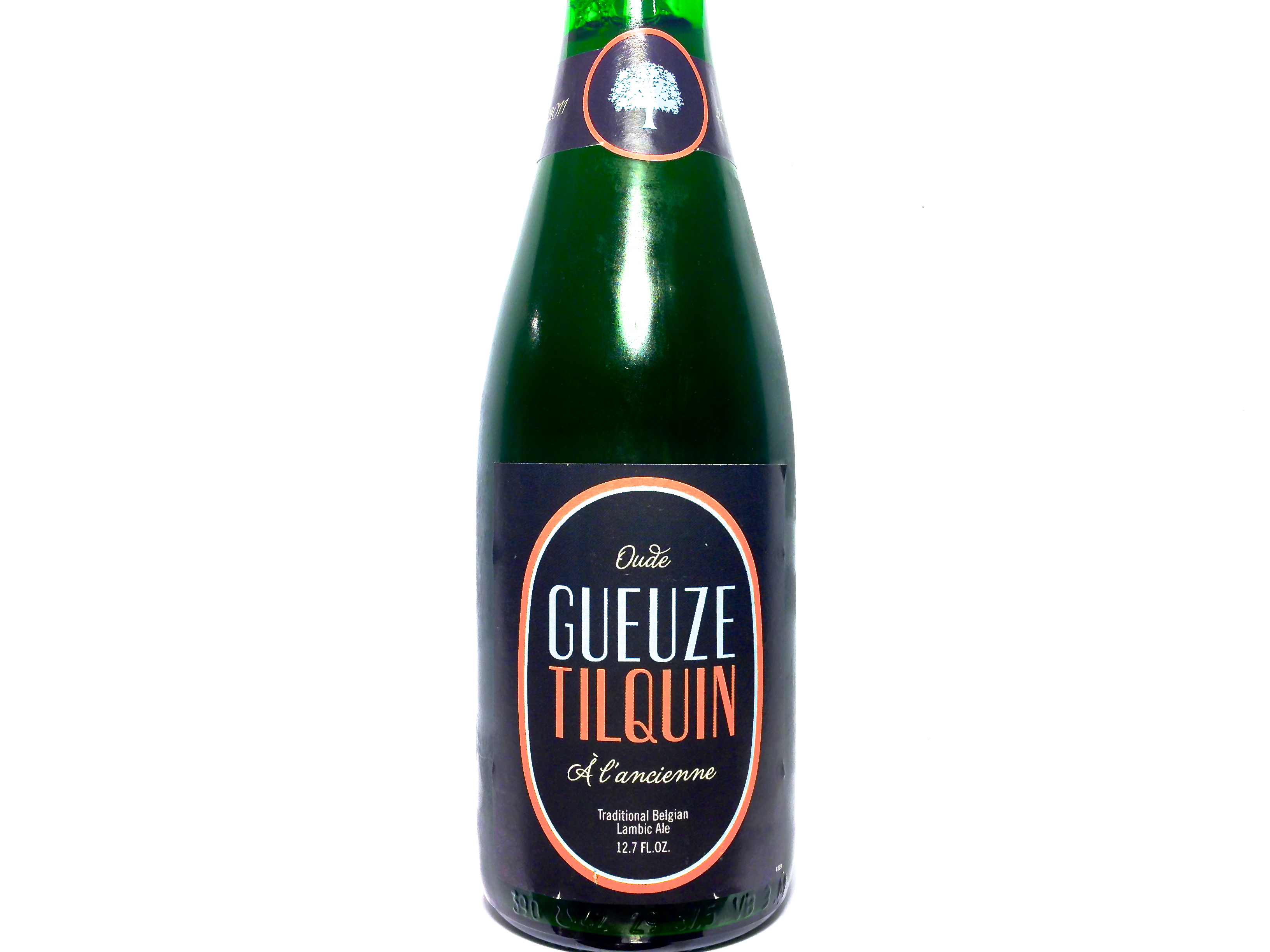

As I’m writing this, I’m drinking an Oude Gueuze Tilquin à I’Ancienne. The aroma is like smelling a grapefruit peel, with a bit of an added mustiness, and a slight wood like aroma. The initial up front flavor is mix of various citrus fruits, like grapefruit, lemon, and lime, but it then fades and reveals various other fruits as well. Fruits like green apples, and berries like tart cherry become more present towards the finish. The beer has a champagne like carbonation and it gives the beer a dry and crisp finish. The finish shows off it’s musty, barnyard like qualities that fade into a lingering sweetness that resembles the sweetness in an orange.

I fully admit that the first time you try a sour beer, you may not like it. It is difficult to prepare yourself for something like it. The first time I had New Belgium’s La Folie, I had a difficult time finishing it. Now I can’t get enough. Like most things in life, it is an acquired taste. However once you acquire it, you can never let it go! Gueuze, though hard to find in Las Vegas, are a good start since they are a bit balanced in their flavor. Jolly Pumpkin makes several approachable sour beers as well. Something like Bam Bière isn’t exactly sour, more so a little tart. This will start to build your tolerance and acceptance for acidity in beer. Work your way up to something like La Folie. It’s a deliciously complex beer, but it is intense in it’s sourness!

Glassware is one of the most under appreciated aspects of enjoying craft beer. That truth is however, that glassware is probably one of the most important factors in whether a beer can be found enjoyable or not.

First, it is important to understand how vital aroma is to contributing to flavor perception. The human tongue is only capable of discerning five different tastes (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami). But if these are the only tastes that we can detect, how is it that we can perceive the difference between one beer to the next? Our sense of smell, on the other hand, can detect between 4,000 and 10,000 different odor molecules! Our perception of flavor is in part determined by what our tongue tastes, but also the smells that our nasal passage detects.

If you want to truly taste a beer to the fullest, inhale through your nose as you are drinking, hold your breath as you taste it in your mouth, and breath out your nose after you swallow. By drinking beer this way, you are taking in the aroma and smell of the beer as you are drinking and after you swallow, you are allowing the aroma to travel back though your nasal passage so you can get a good sense of it’s aftertaste.

So, now that you know how important your sense of smell is, why does glassware matter? You want something that is going to allow you the best possible experience of being able to smell and take in the aroma of you beer. How well do you think you can smell your beer by drinking out of the bottle?

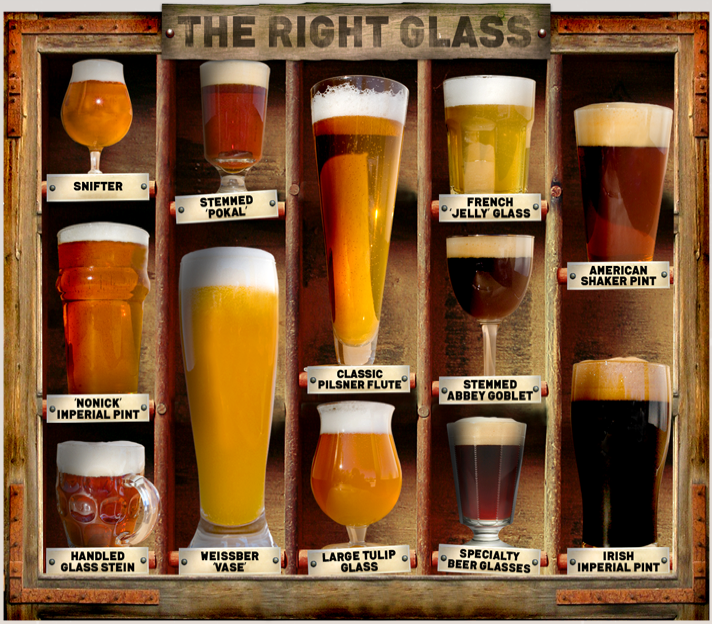

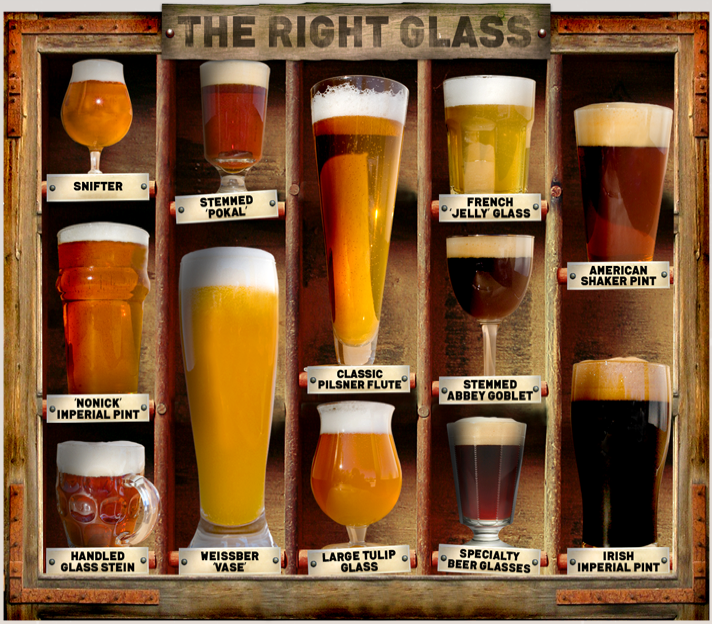

Aside from contributing to aroma perception, proper glassware also depends on the style of beer you are drinking. The above image is taken from craftbeer.com This link is a great resource for learning and understanding what glassware best compliments which style of beer. I highly recommend checking it out.

The Saccharomyces brothers, Pastorianus and Cerevisiae, are recognized as being the lager and ale yeasts of beer production. While they have been doing a good job of creating dozens of different, recognized styles of beer, it seems brewers are looking to a new yeast to do their bidding.

The Saccharomyces brothers, Pastorianus and Cerevisiae, are recognized as being the lager and ale yeasts of beer production. While they have been doing a good job of creating dozens of different, recognized styles of beer, it seems brewers are looking to a new yeast to do their bidding.

Now it’s the Brettanomyces family of yeasts that are getting all the attention. It seems these days that if you want to stand out amongst the nearly 2,000 breweries in America, you need to either barrel age your beer, add wild yeasts to the fermentation, or both. “Brett” is the new buzzword amongst craft beer followers. There’s no limit as to what beers you can spike with Brettanomyces. Lambics, farmhouse ales, saisons, etc are the standard. But breweries like Anchorage, Jolly Pumpkin, and The Bruery are putting Brettanomyces in white ales, IPAs, and even stouts!

Flavors of Brett fermented beers range and vary depending on the strain of Brett used and whether it is used in primary fermentation or in a secondary fermentation. You may either not notice a difference in a beer with Brett, or it may be a little tart and fruity, or very funky with complex aromas and flavors of a wet horse blanket (appetizing, right?).

I am not very well versed when it comes to Brettanomyces in beers. If you want more information, I highly recommend you check out Embrace The Funk’s website.

If you want to buy a few Brett beers in Las Vegas, check out Whole Foods or Khoury’s Fine Wine. Both tend to have a very good selection of Brett fermented beers.

Trying to explain yeast and what it does is much more difficult than trying to explain the other components of beer. Because of this, I have broken up my discussion of yeast into several posts. This is the third and last post in which I describe what affects fermentation.

As previously discussed, both species of beer yeast consume sugars and leave alcohol and carbon dioxide as waste products. I also mentioned previously that the process of fermentation was seen as a gift from god by early civilizations due to their lack of knowledge in unicellular microorganisms. Even today, with this understanding, it is also understood that brewers make wort, yeast make beer. Understanding what affects the yeast to do its job is what allows us today to successfully ferment at an expected level.

It is important to remember that yeast is a living organism, just like humans. While we have human civilizations living all across the world, there are certain conditions that must be met to allow us to survive and live in extreme conditions. If our body temperature gets too cold or too hot, we die. While humans can live and grow eating poor quality, empty calories, we can grow healthier and stronger with proper nutrition. It is also important that we are protected from bacteria and toxins which harm us, even one’s that our body produces.

Each strain of yeast has a temperature range in which it prefers to exist in. In general, lagers are known for their cold fermentation temperatures, in the 40’s-60’s (fahrenheit). Ales however, are known for their warmer temperature ranges, from the 60’s-70’s. The specific range that a given strain is meant to ferment at, ensures that the yeast remain healthy and actively consuming sugars. Should the temperature get too low, the yeast goes dormant and stops fermenting. Should the yeast get too hot, it will still ferment, however it will produce off-flavors that are not ideal to the flavor of the beer. To compare it in human terms, if you get too cold, you get hypothermia and go dormant (in a sense). Or compare doing housework inside your air-conditioned home as opposed to doing yard work in the middle of summer. You won’t die working outside, but you will smell a lot worse!

While yeast consumes sugar as it’s main diet, there are important other minerals that keep the yeast healthy enough to keep consuming sugar, much like us humans need adequate amounts of the appropriate vitamins and minerals in our diet. In the case of yeast, calcium, magnesium and zinc are important. Magnesium, for example, allows for better cellular metabolism, allowing the yeast to convert energy to continue consuming as well as reproduce. Some of these nutrients come from the malt and some come from the water. The water is an area that many people do no consider enough in beer making. Purified water is not ideal in brewing as it has been cleaned of all it’s minerals. Chlorinated water affects the yeasts ability to live and properly grow. Besides affecting the yeast, water chemistry also alters the mashes conversion of starch into sugar and the affect hops have in beer.

Lastly, while we may enjoy the alcohol and carbon dioxide in beer, remember that those are waste products to yeast. Imagine for a moment if you were trapped in a jail cell with no toilet. Yeah, exactly. Different yeast strains have difference tolerance levels for alcohol. If a particular strain doesn’t have a very high tolerance, than it won’t be ideal to use when making a barley wine. Instead of a high alcohol beer, the yeast will die off as the alcohol content rises leaving you a beer that has less alcohol and tastes rather sweet. Even commercial breweries like Dogfish Head have difficulty when making their 20% 120 Minute IPA. On the TV show Brewmasters, Dogfish Head was forced to dump an entire batch due to the yeast not finishing the fermentation.

Whether you are brewing a high alcohol beer, a lower session-style beer, it is important to consider all of these facts when it comes to brewing. Use a strain that’s best suited for the style being made. Ensure that you have the means to keep the yeast at the correct temperature specified for a given strain. Most people make a yeast starter, which is essentially a small batch of beer made for the same purpose that sports teams have pre-season games. It gets the yeast started fermenting and reproducing so it can be strong and ready for the main event. The higher the alcohol the beer will be, the more yeast will need to used. Consider trying to build a house by yourself as opposed to entire team of people. Sure you might be able to finish the house alone, but it’s going to take much longer and likely be of a lesser quality than one built by 10 people.

There is still much more to be said about yeast and it’s affects on beer making. As I mentioned a few times, while there are two main species of yeast, there are over a hundred strains within those two species, each with different levels of attenuation, flocculation and alcohol tolerance. All yeast give off different levels of the off-flavors that are a part of normal fermentation. In some strains of yeast it may be more of a particular flavor, that is best suited for one style of beer, but not another. In addition to these two species of yeast, there are other wild yeast strains that are used for the affects that they have on beer. For example the brettanomyces strains can consume even more polysaccharides than ale or lager yeast can, and it also produces some tart flavors. Some brewers will add this after completing a fermentation with an ale yeast, or some may completely ferment a beer using only this yeast. There are endless possibilities. To be a great brewer, you must truly understand how to use yeast.

Trying to explain yeast and what it does is much more difficult than trying to explain the other components of beer. Because of this, I have broken up my discussion of yeast into several posts. This is the second post in which I describe what yeast does.

In the first post on yeast I described the two types of yeast, ale and lager yeast. To explain the differences, I first want to explain the purpose of yeast in the process of making beer, or any other alcohol for that matter.

Ethanol Fermentation: Ethanol is the type of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages. Yeast produce alcohol and carbon dioxide as a waste product of consuming sugar. Chemically, one part glucose (a simple sugar molecule) is broken up and converted into two parts ethanol and two parts carbon dioxide. The balanced chemical equation looks like this:

C6H12O6 —> 2C2H5OH + 2CO2

In the case of bread making, the carbon dioxide is what causes the dough to rise and the ethanol gets evaporated when baked. In beer making, the ethanol and carbon dioxide stay in the beer with the carbon dioxide being the source of carbonation.

While the above equation shows the fermentation process of a simple glucose molecule, not all sugars are that simple. The above glucose molecule is called a monosaccharide. More complex sugars form compounds called disaccharides or trisaccharides. Whereas all the monosaccharides and disaccharides will be fermented, the trisaccharides and larger polysaccharides are another story.

Prior to the beginning of fermentation, brewers measure the density of the wort. It’s the sugar within the liquid that causes the wort to be denser than pure water. As the yeast consume the sugars, the density drops, though never all the way down since the complex polysaccharides are more than the yeast can handle. The amount that a strain of yeast can decrease the density of the wort is called attenuation. Lager yeast typically has a higher attenuation than ale yeast, meaning that more of the larger polysaccharides get consumed into alcohol and carbon dioxide. The result of this is that lagers are known for their dry, crisp taste and feel whereas ales leave more residual sugar behind giving them a bit more of a complex taste that is typically described as fruity.

As the yeast is actively consuming sugar, they are simultaneously multiplying as well. The amount of yeast within the vessel increases. When using ale yeast strains, the yeast all rise to the top of the wort. Lager yeast, on the other hand, sink to the bottom of the vessel. For this reason, ale yeast is often called top fermenting yeast and lager yeast is called bottom fermenting yeast.

Once fermentation is complete, any yeast suspended in the beer clumps together and sinks to the bottom as it becomes dormant. The amount that the yeast will clump together and sink is called flocculation. Many beers have a relatively high flocculation rate however the yeast strains used in wheat beers have a low flocculation rate, which is why hefeweizens are cloudy looking.

This was a long article containing lots of big words and chemistry. The next yeast article will focus on the factors that affect fermentation, primarily temperature, which is the last main difference between ale and lager yeasts.

Trying to explain yeast and what it does is much more difficult than trying to explain the other components of beer. Because of this, I have broken up my discussion of yeast into several posts. This is the first post in which I describe what yeast is.

Yeast is the unsung hero in beer making. An old brewing saying goes: “Brewers make wort, but yeast makes beer.” This quote stems from the fact that yeast has the most important job and without it, there is no fermentation and no alcohol. Prior to the discovery of what yeast is, ancient civilizations found the fermentation process to be a gift from the gods since the process was seemingly out of their control. You can’t force the yeast to ferment, it is a living organism and can at times be difficult to deal with.

So what is yeast? Yeast is a unicellular microorganism in the fungus family. While there are 1,500 different species of yeast, brewers are concerned only with 2: Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pastorianus. They are also known by their easier to pronounce nicknames: ale yeast and lager yeast.

All beers are either an ale or a lager. The differentiating factor between the two is determined by what species of yeast is used, saccharomyces cerevisiae being the ale yeast and saccharomyces pastorianus being the lager yeast. Within these two species are many strains of yeast.

To understand what the differences are between these two species of yeast are, it is best to understand what it is that yeast does to wort and what affects its ability to do so. In the next article, I’ll detail the purpose of yeast.

This article was previously posted on the Examiner as part of my Science of Beer series.

This is part two of a multi-part article on the science behind making beer.

Beer is composed of only four ingredients: water, barley, hops, and yeast. Hops are the one ingredient that most people know the least of. Why are they added to beer? What is their purpose?

Hop plants are part of the hemp family Cannabinaceae. The Cannabinaceae family then breaks down into two genera: Cannabis, from which hemp fibers and marijuana come from, and Humulus. The Humulus genus is where hops come from. The Humulus genus breaks down into three different species, two of which are different Asian hop varieties and then there is Humulus lupulus, which containes the European and American hop varieties that are typically used in beer production.

Hop plants grow as a bine, similar to a vine however its method of climbing and attaching itself is different. The female hop plants create a flower cluster called a seed cone. This cone is similar in shape and purpose to other plant cones, like pine cones. However hop cones are green, soft and very leafy as opposed to the rigidness of the pine cone. These cones are the parts of the plant that are plucked and used in beer.

When brewing beer, malted barley is mashed in hot water to extract the sugars. The sugar water, called wort, is then drained where it moves to the next part of the process, the boil. Wort is boiled for about an hour for the purpose of both sanitizing it, and to boil off some of the water leaving the sugar concentration higher. It is during this boil that hops are added as well.

Hops serve three different purposes in beer: adding bitterness to balance out the sweetness in the wort, adding a pleasant aroma to the beer, and to prevent spoilage.

Hops contain an internal resin that contains both alpha and beta acids. Alpha acids contribute bitterness and beta acids contribute aroma. Thus the varieties of hops that contain high levels of alpha acids are called bittering hops and the varieties that contain higher levels of beta acids are called aroma hops. Bittering hops are added earlier in the boil because the alpha acids need heat to break down and be released. The earlier in the boil they are added, the more heat is added and thus the higher level of bitterness is added to the wort. Beta acids, on the otherhand, do not need heat to be released so aroma hops are added at the very end of the boil or even during the fermentation process. Adding hops during fermentation is called dry-hopping and is done regularly in many ale styles. Adding aroma hops during the end of the boil or during fermentation adds only more hop aroma without adding additional bitterness.

Lastly, hops help to prevent spoilage in beer. The alpha acids have a natural antibiotic and antibacterial quality to them. Prior to beer production, hops were used as a form of medicine because of these qualities. The antibacterialness of hops was realized when Britian began trading with India. Beer was produced and brought aboard ships for the sailers to drink during the voyage to India. By the end of the trip, most of the beer had been spoiled. However the beers that had hops used instead of other bittering herbs were not spoiled since any bacteria it came in contact with were killed by the alpha acids in the hops. Thus more hops were added to beer to ensure it would would not spoil during the trip to India; and with that the IPA, or India Pale Ale style was born!

Once the boil is complete and hops are added, the wort is then chilled and yeast is added to ferment. Yeast and fermentation will be discussed in a future article.

This article was previously posted on the Examiner as part of my Science of Beer series.

This is part one of what will become a multi-article study into the science behind making beer.

Apart from water, barley is the main ingredient in beer. The barley is what determines the color and primary taste as well as dictates how much alcohol will be present within the beer in the end.

To create malt, barley grains combine with just enough water that they begin to germinate as though they are being planted into the ground. When barley begins to germinate, it releases an enzyme called amylase. The purpose of amylase is to break down the starches within the barley into smaller carbohydrates that can be used as an energy source for the sprouting plantlet. Human saliva also contains amylase to begin breaking down the food we eat before entering the stomach. Without amylase to break down the carbohydrates, sugars cannot be extracted from the barley to later be converted into alcohol.

In order to stop the germination process, heat is applied to the barley to completely dry it out. This process can be done in a number of different ways and is what differentiates one type of malt from another. Either the heat can be slowly and gradually added to the malt, leaving the color pale with no noticeable roasted characteristics, or it can be left heated long enough that the barley darkens and turns various shades of brown or even becomes blackened. Another common method is to add a very high heat very quickly to caramelize the outer edge into a reddish color. Depending on the combination of malts used in a brewing recipe, the flavor and color of the beer can be determined.

Breweries typically purchase barley already malted and will then begin the first step of creating beer, mashing. Mashing involves milling the grain and letting it soak in hot water, typically around 150 degrees Fahrenheit, for about an hour. The ultimate goal in mashing is to release the sugars from the malt into the water creating a sweet liquid called wort. Wort is simply unfermented beer. Later when yeast is added to the wort, sugars are converted in alcohol and thus wort becomes beer.

The amount of malt used in a beer will vary from one recipe to the next. Since the purpose of malt is to release sugars that later get converted into alcohol, you would typically add more malt if you want more sugars, and in turn, more alcohol. For 5% alcohol by volume beer, you would use about one pound of malt for four pints. If this beer were to be one 15 gallon keg of beer, about 30 pounds of barley would need to be mashed.

Once the malt is mashed, the wort is drained from the grains and moved on to be boiled and have the hops added. This will be discussed further in a future article on hops.

Last night at the bar it was mentioned that many people don’t realize how many different types of beer there are. I thought I’d give a brief overview:

To simplify things, there are primarily two different types of beer: Ales and Lagers. At the most basic level, the difference between the two is the type of yeast used to ferment the beer. Lager yeast ferments at colder temperatures and ale yeast ferments at higher temperatures. Lagers and ales break down even further into different types of beers.

Lager:

This is the most prominent type of beer simply because this is the kind of beer that Budweiser, Miller and Coors are. Other common lagers are the popular Mexican beers: Corona, Dos Equis, Pacifico etc. These beers are best served at ice cold temperature and as such have a lighter more “refreshing” taste. Or as I think of it, kind of watered down taste. The predominant lager beers are American lagers and pilsners. Again simply because this is what the big 3 companies make. The good lagers are the kind that Germany makes: marzen, bock and dunkel. These beers are typically darker colored and have a much more complex taste than the common American lager. However these beers are still lighter in flavor and feel than most ales and don’t have a predominant hop taste.

Ales:

These are the more complex beers with a wider range of style. These range from the wheaty Hefeweizen and white beers (like Pyramid Hefeweizen or Blue Moon) to the dark stouts (like Guinness). Pale ales and India pale ales sit in the middle of the spectrum. IPAs and pale ales are recognized by their hoppy bite. Ales are the predominant type of beer everywhere except North America. I couldn’t begin to try and explain every type of ale because there is just so many kinds!

Ales are by far, my favorite kind of beer just because there are so many different kinds. The few beers that ive blogged about here have all been ales. I’ll try to continue to review different beers and use that opportunity to describe the beer type and it’s common characteristics.